On the Real Watership Down

Richard Adams’ Grave

The most poignant location to end your journey around the landscape of Watership Down.

They went out past the young sentry, who paid the visitor no attention. The sun was shining and in spite of the cold there were a few bucks and does at silflay, keeping out of the wind as they nibbled the shoots of spring grass. It seemed to Hazel that he would not be needing his body any more, so he left it lying on the edge of the ditch, but stopped for a moment to watch his rabbits and to try to get used to the extraordinary feeling that strength and speed were flowing inexhaustibly out of him into their sleek young bodies and healthy senses.

‘You needn’t worry about them,’ said his companion. ‘They’ll be all right—and thousands like them. If you’ll come along, I’ll show you what I mean.’

He reached the top of the bank in a single, powerful leap. Hazel followed; and together they slipped away, running easily down through the wood, where the first primroses were beginning to bloom.

Epilogue

Richard Adams, author of Watership Down, died at 10pm on Christmas Eve, 2016.

Beyond his best known work, Adams wrote a follow-up of short stories, Tales From Watership Down, an autobiography, The Day Gone By, and a string of fictional novels. The best of the novels, at least in my eyes, is The Plague Dogs—the story of two dogs who escape a state-run animal testing laboratory in the hope of finding a better life.

Richard Adams’ former home in Whitchurch, behind the two parked cars on the left.

Born in 1920, Adams had spent his early years living in a Wash Common, then a distinct village to the south of Newbury. The house, Oakdene, sat between the Andover Road and Monkey Lane (now Monk’s Lane) and was just a short walk from Sandleford Park where Watership Down begins. In his autobiography, The Days Gone By, Adams wrote:

‘There were three acres of land altogether and a gardener’s cottage, which had its own small garden. The superb view to the south was across the open country of ploughland, meadows and copses typical of the Berkshire-Hampshire border, stretching away four or five miles to the distant line of the Hampshire Downs—the steep escarpment formed by Cottington’s Hill, Cannon Heath Down, Watership Down and Ladle Hill’.

Whilst Oakdene may have been replaced by more modern housing, and Wash Common is now a suburban area, the places on that escarpment remain. They never left Adams and he drew upon them as the principle setting for Watership Down whilst working as a civil servant.

For more than twenty years before his death, Adams lived at 26 Church Street in Whitchurch, a small town aptly sited on the River Test, not too far from the real Watership Down. His residence was just a short walk from the small cemetery where he is buried, on the road that takes the traveller to Andover.

The final resting place of Richard Adams and his wife Elizabeth: Whitchurch Cemetery, Hampshire.

Whitchurch Cemetery is, like many other small town burial grounds, routine and unspectacular. Traffic roars by to the west on an elevated section of the A34 and, to the north, two new housing developments have taken the town’s perimeter all the way up to the dual-carriageway. Both are Watership Down themed: Owsla Park and Watership Place. Whilst the latter possesses the likes of Richard Adams Way, Buckthorn Road and Bluebell Place, Bewley Homes missed a good opportunity for Holly Avenue, Campion Close and Thlayli Drive at Owsla Park, instead opting for bird names and a nod to Caesar’s Belt.

Presumably, the developer here, just as that at Sandleford Park, missed the dismal irony in linking new housing estates to a novel built around the destructive effects of such development.

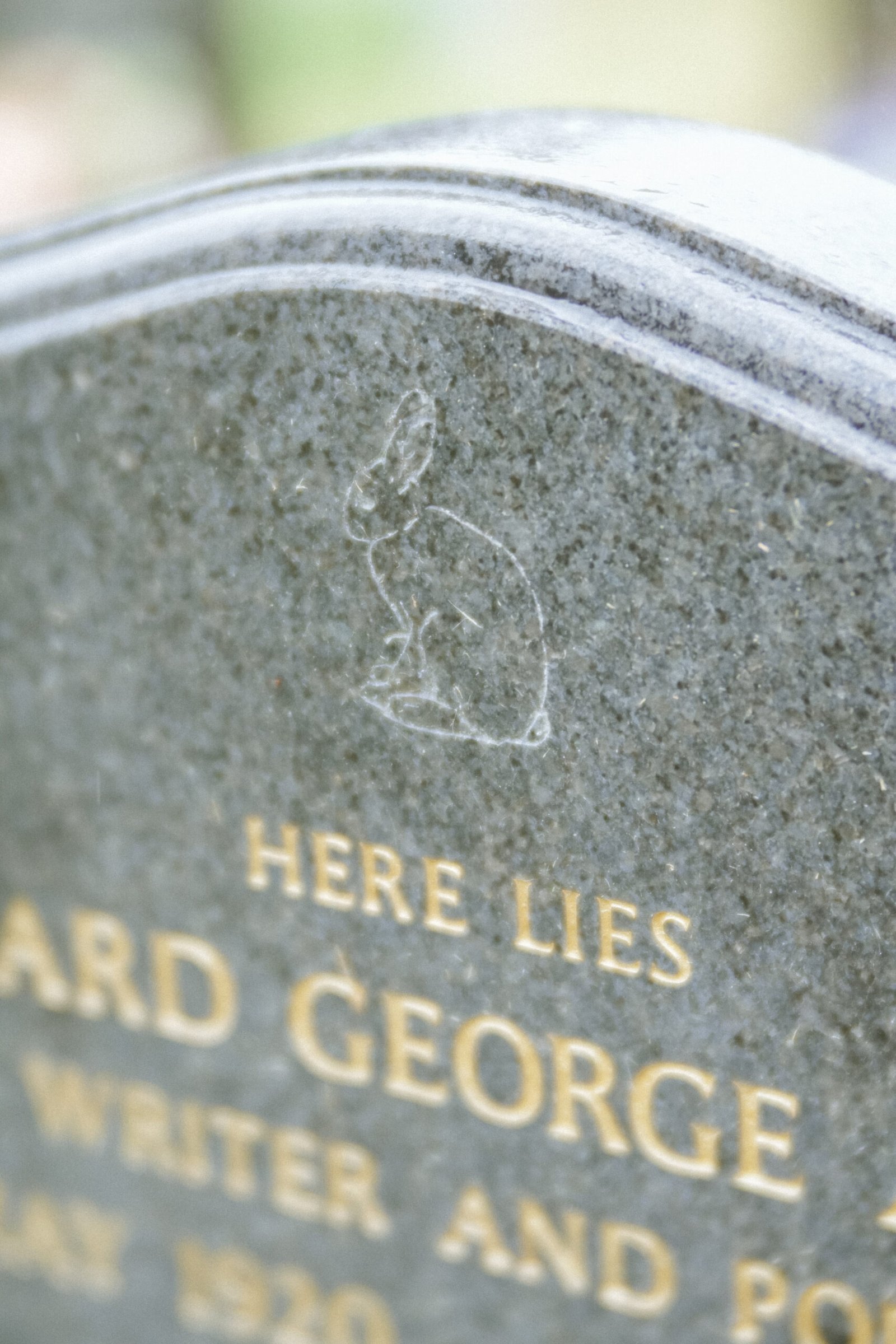

Detail of the rabbit at the top of the gravestone. Taken May 2025.

I made my way to Whitchurch Cemetery in March 2025. I scanned neat rows of graves for a good ten minutes before finding the headstone of Richard and Elizabeth Adams. Positioned close to the back gate, it’s so understated I had walked past it twice without noticing it. What eventually gave the game away was the white and brown ceramic rabbit that been left on the base of the gravestone; possessing an optimistic smile it sat alongside a more pensive, smaller and appropriately black companion. If I had to choose just one adjective to describe the memorial it would be ‘dignified’.

As a neighbour set to moving things in and out of her front door, I struggled to get a photo of the grave, having only brought my 85mm lens with me on my camera. Just as I was reframing the shot, I caught an unexpected movement from the peripheral vision in my left eye. Streaking along the path not far in front of me was a beautiful, grey, wild rabbit, dashing with all four feet in the air. It continued its sprint all the way to the hedge line, re-emerging to gallop down to the embankment alongside the A34.

An elderly man nearby, tending to another grave, had also seen the rabbit. He called over to me next to the Adams grave and laughed, ‘Maybe he knew you were coming?’

Maybe. I would like to think so.