On the Real Watership Down

Cowslip’s Warren

The Sandleford rabbits attempt to assimilate into the strange culture of a warren that hides an appalling secret.

The corner of the opposite wood turned out to be an acute point. Beyond it, the ditch and trees curved back again in a re-entrant, so that the field formed a bay with a bank running all the way round. It was evident now why Cowslip, when he left them, had gone among the trees. He had simply run in a direct line from their holes to his own, passing on his way through the narrow strip of woodland that lay between.

Indeed, as Hazel turned the point and stopped to look about him, he could see the place where Cowslip must have come out. A clear rabbit-track led from the bracken, under the fence and into the field. In the bank on the further side of the bay the rabbit-holes were plain to see, showing dark and distinct in the bare ground. It was as conspicuous a warren as could well be imagined.

Chapter Thirteen—Hospitality.

In Chapter Twelve, The Stranger In The Field, the Sandleford rabbits leave the heather and unwelcoming woodland of Newtown Common behind them, breaking into beautiful open meadows and long grass. Keen to remain in such a beautiful location, the rabbits begin to scrape shallow holes close to an oak tree between two copses. These two pieces of woodland are divided by a brook. With rain imminent, the light-hearted digging is interrupted by a large, well kept rabbit sat in front of the opposite area of woodland. He introduces himself as Cowslip, and invites the hlessil to stay in his warren’s numerous ’empty burrows’. The travellers are non-committal and Cowslip heads back to his warren, the offer still open.

As the rain begins to pour, the rabbits are beautifully described by Richard Adams as ‘a muddy handful of scratchers, crouching in a narrow, draughty pit in lonely country. They were not out of the weather. They were waiting, uncomfortably, for the weather to change.’ They need no persuasion to accept Cowslip’s proposal. Only Fiver protests, as if he senses something is badly wrong, not that he is entirely certain of the source of his fears.

The subsequent five chapters reveal the chillingly eerie denialism of the warren’s inhabitants in the face of an unspoken secret they all share and accept. It is only when Bigwig is almost killed in a snare (Chapter Seventeen, The Shining Wire) that things become clearer and the Sandleford rabbits flee.

The film’s coverage of this sequence is condensed, but the essential truths remain. And who can forget the infamous scene in which Bigwig chokes blood in the snare as flies swarm around his suffocating body?

Bigwig wishes he had listened to Fiver’s protests … each and every one.

It’s a tough scene to watch, and almost as difficult as trying to uncover the real location in which the Warren of the Snares, or Cowslip’s Warren—call it what you will—was situated. As such, I am extremely thankful to Aldo Galli, a friend of Richard Adams whose beautiful paintings accompany the illustrated edition of the novel from 2014, for providing much needed clarity.

The Journey to Burghclere

The rabbits’ travels took them roughly south-south-west from Newtown Church and through the dense, alien undergrowth of Newtown Common. Geographical reality means they would also have passed through Burghclere Common and part of Herbert Plantation which, until it was entirely planted up with trees in the late 1950s, contained significant areas of rough grass and heath. The open meadowland which the rabbits subsequently find themselves in is just to the east of the pretty village of Burghclere and south of the hamlet of Adbury and its country estate.

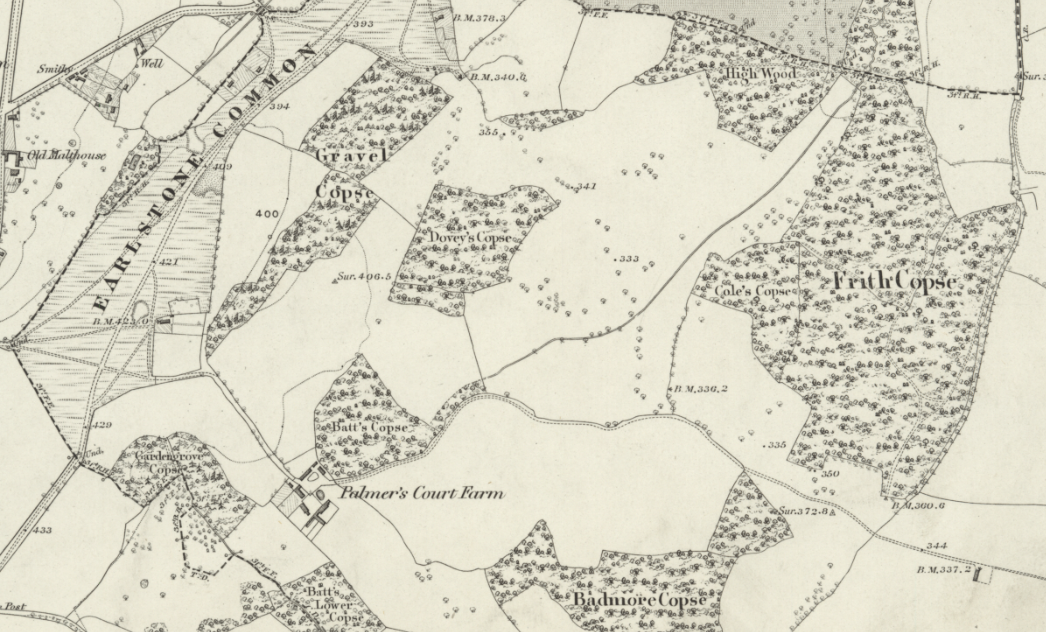

We can get a decent overview of the area from this 1888-1915 Ordnance Survey map (below). Whilst the map predates the story of Watership Down, little changed on the landscape until the end of the 1960s.

The 1888-1915 Ordnance Survey map of the landscape around Cowslip’s Warren.

Scratchings

After entering the area from the north-west, the rabbits find the brook. Dandelion observes that rain is on the way and suggests they start to dig scrapes for shelter. They split into two groups, as stated in Chapter Twelve, Hospitality:

Hazel led the other rabbits across the field and up to the edge of the woodland. They went slowly along the foot of the bank, pushing in and out of the clumps of red campion and ragged robin. From time to time one or another would begin to scrape in the gravelly bank, or venture a little way in among the trees and nut-bushes to scuffle in the leaf-mould. After they had been searching and moving on quietly for some time, they reached a place from which they could see that the field below them broadened out. Both on their own side and opposite, the wood-edges curved outwards, away from the brook. They also noticed the roofs of a farm, but some distance off. Hazel stopped and they gathered round him.

‘I don’t think it makes much difference where we do a bit of scratching,’ he said.’ It’s all good, so far as I can see. Not the slightest trace of elil – no scent or tracks or droppings. That seems unusual, but it may be just that the home warren attracted more elil than other places. Anyway, we ought to do well here. Now I’ll tell you what seems the right thing to me. Let’s go back a little way, between the woods, and have a scratch near that oak tree there – just by that white patch of stitchwort. I know the farm’s a long way off, but there’s no point in being nearer to it than we need. And if we’re fairly close to the wood opposite, the trees will help to break the wind a bit in winter.’

Later, during the Sandleford hlessil’s initial meeting with Cowslip, the latter is unimpressed with Hazel’s choice:

These scrapes aren’t very deep or comfortable, are they? And although they’re facing out of the wind now, you ought to know that this isn’t the usual wind we get here. It’s blowing up this rain from the south. We usually have a west wind and it’ll go straight into these holes.

Aldo Galli recalls from conversations with Richard Adams that the scratchings were located close to High Wood. Given their exposure to westerly winds, Hazel has chosen a site somewhere along the woodland’s southern flank. Perhaps it is noteworthy that the 1888-1915 Ordnance Survey map shows some solitary (or very small clusters of) trees to the east of the triangular indentation in High Wood. Whether the westernmost of these was the oak tree in question I don’t know—the 1942 map betrays Ordnance Survey’s shift away from detailing such small features dotting the landscape—but it’s a reasonable guess.

The site of Cowslip’s warren in July 2025, positioned in the treeline, above the solitary tree that is to the right of centre. High Wood is to the left. My guess is the scrapes were near the tree closest to the bottom-left of the image.

A slightly wider shot with a better view of High Wood on the left. November 2025.

Cowslip’s Warren

Within Chapter Thirteen, the rabbits accept Cowslip’s offer of shelter and make their way over to the warren:

The corner of the opposite wood turned out to be an acute point. Beyond it, the ditch and trees curved back again in a re-entrant, so that the field formed a bay with a bank running all the way round. It was evident now why Cowslip, when he left them, had gone among the trees. He had simply run in a direct line from their holes to his own, passing on his way through the narrow strip of woodland that lay between. Indeed, as Hazel turned the point and stopped to look about him, he could see the place where Cowslip must have come out. A clear rabbit-track led from the bracken, under the fence and into the field. In the bank on the further side of the bay the rabbit-holes were plain to see, showing dark and distinct in the bare ground. It was as conspicuous a warren as could well be imagined.

The re-entrant is formed by the entire eastern edge of High Wood and the western flank of Frith Copse, directly opposite. It is along the latter where the rabbit holes are so clearly visible in the text.

In real life, modern agricultural practices have seen some noteworthy changes around the Warren site. The brook that divided High Wood and Frith Copse has been diverted up against the eastern edge of the former where it now stops. The touching point of these two woodlands, together with the copse directly north has been cleared of trees to create a thin arable field. Nonetheless, the site of the rabbit holes remains largely as it was when Richard Adams sat down to write Watership Down.

Interestingly, canon lore, based upon Marilyn Hemmett’s grid-style map from the 1972 Rex Collings published original, is that Cowslip’s Warren is located on the south-western edge of that ‘bay’ cutting into the body of High Wood. I will spare readers the minutiae that means this cannot possibly be the case. Maybe another time…

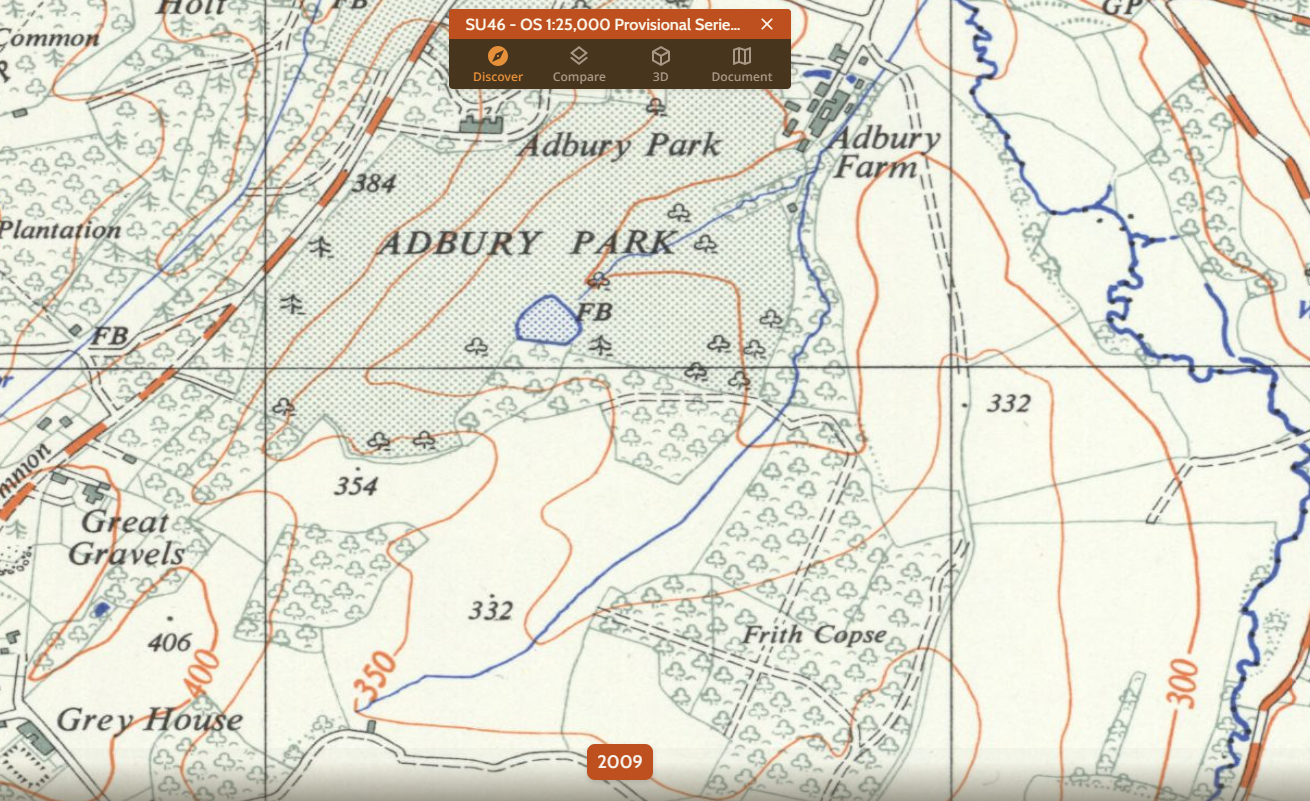

The 1942 Ordnance Survey map showing the area where Cowslip’s Warren was located.

The Snare:

The infamous snaring of Bigwig occurs during Chapter Seventeen after he and Hazel locate an absent Fiver, who is planning to leave Cowslip’s Warren. Fiver is found beyond ‘the hedge beside the carrot-ground and the source of the brook.’

An overhead image from the 1940s shows us this hedge was the boundary that runs due south from the western tip of Cole’s Copse. By 1972 this was accompanied (or replaced) by a ditch that, in turn, was filled in. Today it is possible to see the ground markings of the ditch from above in dry, late summer weather.

Interestingly, the placement of the hedge may potentially leave us with a small geographical error on Adams’s behalf. Bigwig notes that Fiver had passed ‘From the [warren’s entrance] hole straight down towards the brook.’ Both Bigwig and Hazel follow Fiver’s track in the wet grass and subsequently ‘come through the hedge.’ Unless Adams spoke of a hedgerow that was not apparent in the two Ordnance Survey maps and aerial image I’ve studied, none of the rabbits would have needed to pass through this boundary. Fiver was to the west of it, not the east. Nonetheless, it is by passing back through this hedge that Bigwig is snared.

Perhaps Richard Adams was actually referring to the tree-line, marked on more detailed maps (see 1885-1915 map above; these trees were still visible in the aerial image from 1947), which ran northwards, just to the west of of the hedge. All of the rabbits would have needed to pass through this tree-line to reach the flayrah pile and it is not beyond reason that it may have been accompanied by a thin strip of foliage.

Annotated view of the landscape (featuring the Flayrah area and hedge) from above Cole’s Copse. October 2025.

Escape Route:

Finally, for this part of the story, here’s something that’s not in doubt. Following Bigwig’s brush with death in Chapter Seventeen, Fiver persuades the Sandleford rabbits to leave for higher ground. Adams describes the route they took:

South of them, the ground rose gently away from the brook. Along the crest was the line of a cart-track and beyond, a copse. Hazel turned towards it and the rest began to follow him up the slope in ones and twos.

The cart-track in question is now a public footpath, running from Clere School in neighbouring Burghclere, through the old farm that is now called Palmer’s Hill Court, and on to Cow House Lane. The woodland the rabbits subsequently pass through whilst headed south is called Badmore Copse.