Back to the Great Arch

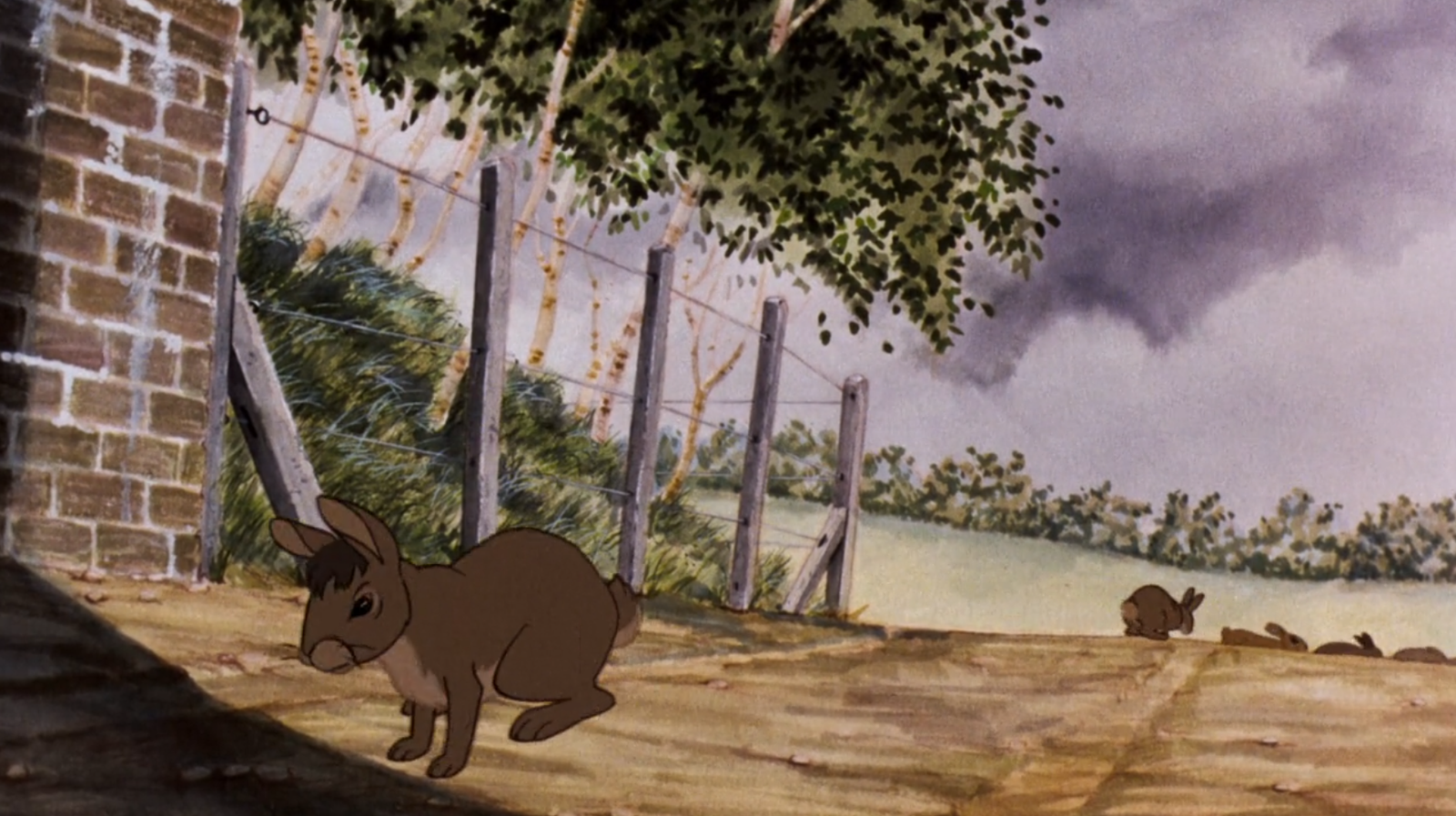

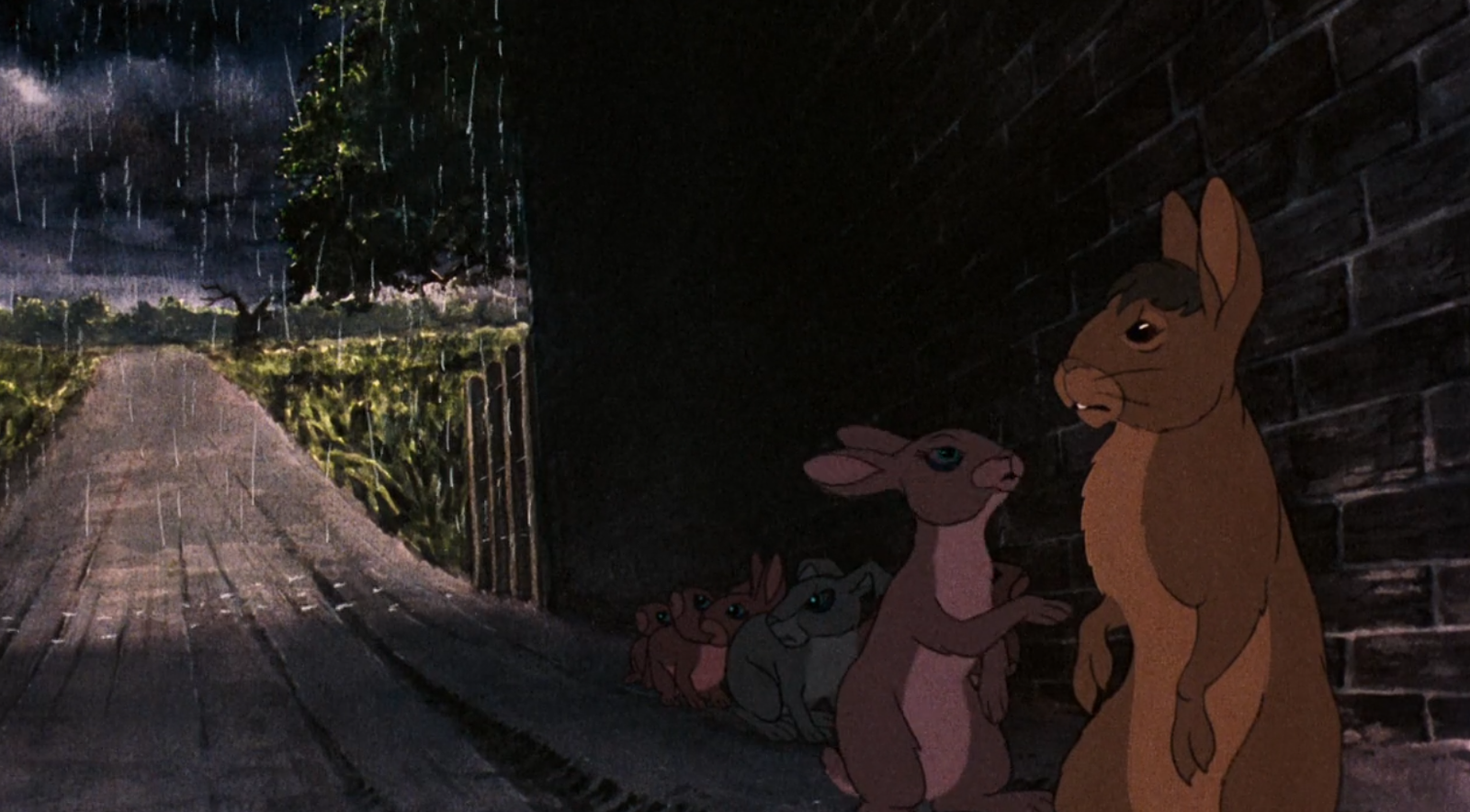

Whilst exploring the stone-chalked writing on the red bricks I was reminded of the scene from the movie where Bigwig, Blackavar and the Efrafan does anxiously wait, sheltered from the hammering storm, for the appearance of Kehaar as their pursuers close in. Some of the females shake from fear. To go back to Efrafa is to return to the cramped, regimented, oppressive realm of Woundwort and the severe punishment that awaits them. To go on is to plunge into an alien landscape. Unless Kehaar shows this journey will be without the benefit of a guide, with capture and sanctioning a realistic prospect. Though, for all of the worry, liberation is there on the horizon.

Of all the man-made features within Watership Down, I am always most drawn to the Great Arch, the railway underbridge west of Overton and south of Efrafa. My recollections of it stretch back 47 years to the time I first saw the film at the cinema. I was fascinated by the arch’s red bricks and the train tracks it supported. That was enough for me, though I liked it that the bad rabbit got jumped by the bird here as well.

In Richard Adams’ writing, the arch is never physically described as anything more than a ‘brick arch in the overgrown railway embankment’ (Chapter Thirty Three, The Great River) with ‘hard, bare earth’ underneath (Chapter Thirty Seven, The Thunder Builds Up). The reader is left to imagine the bricks’ outlines and the mortar used to secure them. Adams’ words leaves us with a structure that is cold, devoid of detail, cavernous and empty. Just a reinforced hole in an embankment.

The arch of the movie is more richly detailed than the one presented in Adams’ manuscript. It is full of character. The individual bricks have been rendered with textural features and the structure feels well maintained. So much so that the largely weed-free edges of the arch at ground level, as well as the track running through it, seem almost too clean.

Spot the difference between the 1978 film and this photo from October 2025.

Within both the novel and the film, the arch represents a significant boundary to be crossed. It indicates both a route to peril and the way to safety. Such places and the choices they present always fascinate me.

In Chapter Thirty Three of the book, it is the departure point for Bigwig on his journey into General Woundwort’s warren. In the following chapter, General Woundwort, we learn that the undesirable ‘wet country beyond’ the arch is seldom patrolled by the Efrafans. Then, in Chapter Thirty Five, Groping, Bigwig tells the escaping Efrafan does, ‘Remember, we go straight down to the great arch on the iron road. My friends will be waiting there. You’ve only to follow me—I’ll lead the way.’ After tumbling down the railway embankment whilst being pursued by Captain Charlock’s Efrafan patrol, Buckthorn, Silver, Strawberry and Holly utilise the ‘tunnel that went right through the bank from one side to the other’ to facilitate both a safe crossing of the track and their subsequent escape back to Watership Down (Chapter Twenty Seven, ‘You Can’t Imagine it Unless You’ve Been There’).

During the movie, the arch takes on a greater significance, with its threshold status being more obvious. For Bigwig it is the entrance to the southern limit of Efrafan influence, where he is immediately accosted by a patrol chasing the rebellious Blackavar. Then, having led a group of escapees back south, the arch becomes a scene of confrontation between Bigwig and Woundwort. This clash is a portent of the epic battle they will later engage in.

Across both representations of the story, Woundwort is prepared to pass through the arch in pursuit of Bigwig, the does and Blackavar. He emerges out onto unfavourable ground where Efrafan familiarity with the soil underfoot is not what it could be. For a character so controlling, the success of the escapees in crossing out of Efrafa and making it to safety is akin to a slap in the face; a direct undermining of Woundwort’s authority. It says something of his hubris that he is later prepared to directly assault the Watership Down warren, the home turf of opponents who have already outwitted him with El-ahrairah’s cunning.

The embankment where Bigwig confronts Woundwort in the 1978 film. Photograph taken October 2025.

On 27th October 2025, with kind permission of the farmer, I was able to revisit the Great Arch.

Turning to face the structure from the north, I grasped the real extent of the similarities between the arch in the film, and how it is today. Whilst the underbridge’s thoroughfare may be a little wider in the movie than reality, Nepenthe Productions delivered a representation of the site that is staggeringly realistic. Rather than dwelling too much on the commonalities, the photographs on this page are illustrative enough to speak for themselves.

Where Bigwig, Hyzenthlay, Blackavar and the does await Kehaar during their escape. Photograph taken October 2025.

On my previous visit I had been a little taken aback by my surroundings. Then I gawped and feverishly took photos. Now, I appreciated where I was and its place in the Watership Down landscape.

To be stood under that tall central arch is to be contained within a little corner of Watership Down liminality. Otherwise surrounded by agricultural land, the arch bears graffiti on the walls that is more significant that I previously thought. Though much has faded or disappeared, it is still possible to make out the names of Kehaar, Thethuthinnang, Fiver and Hyzenthlay. It lends the arch a feeling of being out of place, a location where the banalities of agriculture and functionality cross with the richness of a literary classic. Here you straddle both the mundane and the extraordinary.

Whilst exploring the stone-chalked writing on the red bricks I was reminded of the scene from the movie where Bigwig, Blackavar and the Efrafan does anxiously wait, sheltered from the hammering storm, for the appearance of Kehaar as their pursuers close in. Some of the females shake from fear. To go back to Efrafa is to return to the cramped, regimented, oppressive realm of Woundwort and the severe punishment that awaits them. To go on is to plunge into an alien landscape. Unless Kehaar shows this journey will be without the benefit of a guide, with capture and sanctioning a realistic prospect. Though, for all of the worry, liberation is there on the horizon. Do you become resigned or emboldened? Ultimately, there is nothing left to lose and so the does seize the moment and gamble on their freedom.

Hyzenthlay and Thethuthinnang.

Kehaar.

Perhaps the strongest thing I can say about the Great Arch is that its genius loci (spirit of place) matches that of its representations on paper and celluloid. When a train thunders overhead you hear the sound of the thunder accompanying the breakout from Efrafa. A pair of buzzards seem to constantly hover above, looking for their next meal.

Though the Crixa, the centre of Woundwort’s fiefdom, is only a few minutes’ walk away, that is not a real world place where you can sense the fictional trepidation, fear and anxiety for yourself. It is the same at Cowslip’s Warren where the modern landscape is neat, ordered and idyllic. This railway underbridge is far more atmospheric. It is one of the most monumental features on the story’s real life map.

The Great Arch is on private property. My visit was made with the kind permission of Jackie Crosbie Dawson from Freefolk Farms and Northington Farm.