On the Real Watership Down

The Beech Tree

A young beech tree with fencing that has become a shrine to all things Watership Down.

‘Moving uncertainly in and out along the edge of the hanger, they came to the north-east corner. Here there was a bank from which they looked out over the empty stretches of grass beyond. Fiver, absurdly small beside the hulking Bigwig, turned to Hazel with an air of happy confidence.

‘I’m sure Blackberry’s right, Hazel,’ he said. ‘We ought to do our best to make some holes here. I’m ready to try, anyway.’

The others were taken aback. Pipkin, however, readily joined Hazel at the foot of the bank and soon two or three more began scratching at the light soil. The digging was easy and although they often broke off to feed or merely to sit in the sun, before midday Hazel was out of sight and tunnelling between the tree-roots.’

Chapter Nineteen—Fear In The Dark

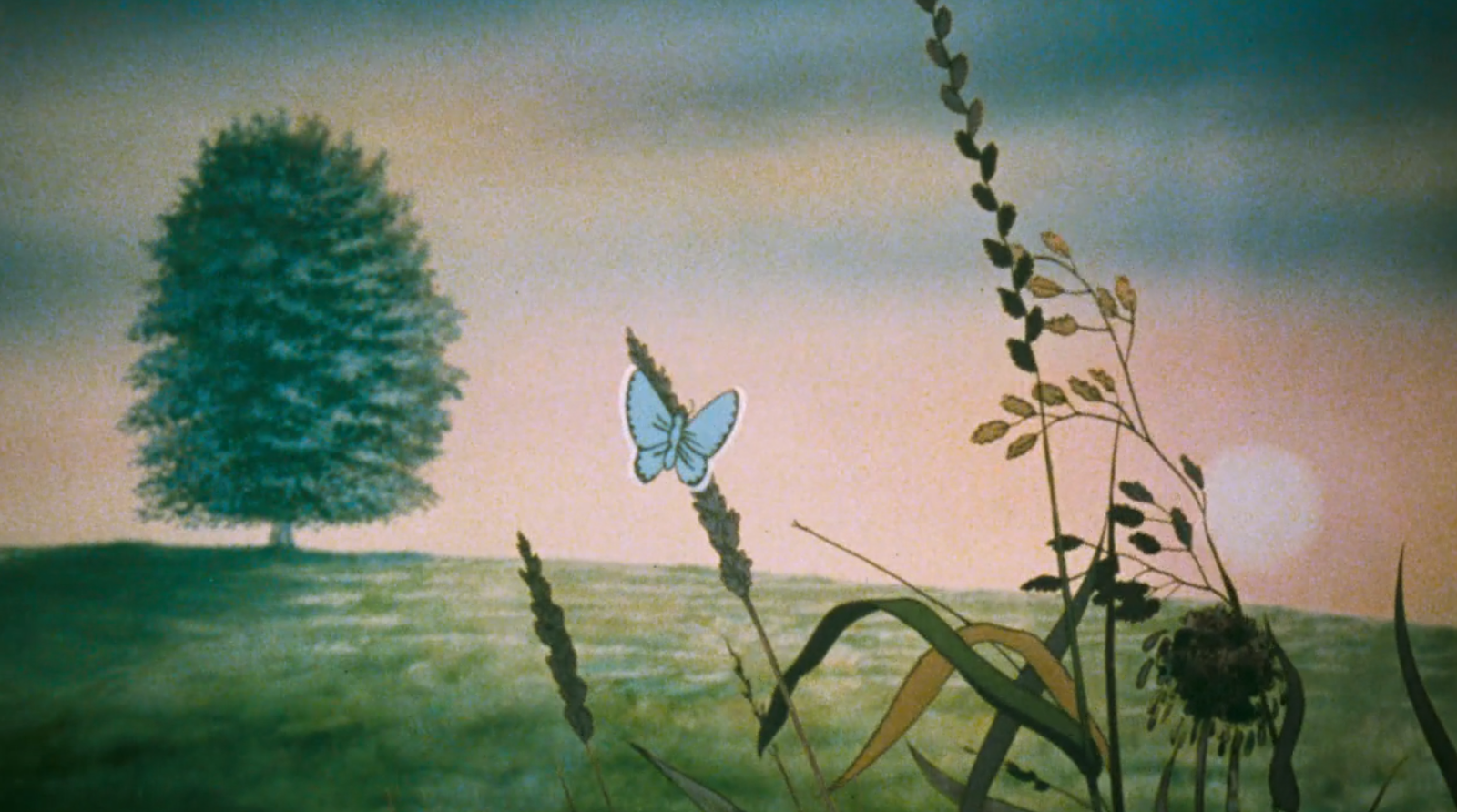

The solitary beech tree of the movie.

On my first visit to the top of Watership Down in 2021 I desperately wanted to find the solitary beech tree that features so prominently in the film. To me, if emphatically symbolises the remote, isolated, hazy beauty of the hilltop in late spring and early summer.

I hadn’t read the book at that point and was a little disappointed to learn that this tree isn’t real. Rather, it’s a representation of the ‘Great Beech‘ that stood at the north-eastern corner of the beech hanger where Adams had set the entrance to the warren. To single out one tree, as opposed to a long avenue of them, is certainly a more powerful visual image.

The beech tree and its fencing have become a shrine for fans of the book and film.

Unfortunately, the ‘Great Beech’ is no longer there, having been brought down during a storm in 2004. To compensate for the loss of this great old tree, a younger sibling was planted next to the footpath in 2013, right in front of the hanger’s north-west corner.

Since it was first erected, the tree’s protective fencing has become a shrine to the book and novel. Visitors have scratched the names of the characters into the wood. Kehaar, Bigwig, Hazel, Fiver and Dandelion are the most prominent at present. Two plaques have also been erected on the fencing. One reads:

In recognition of Richard Adams

‘A lover of Watership Down and its inhabitants’

May 2013

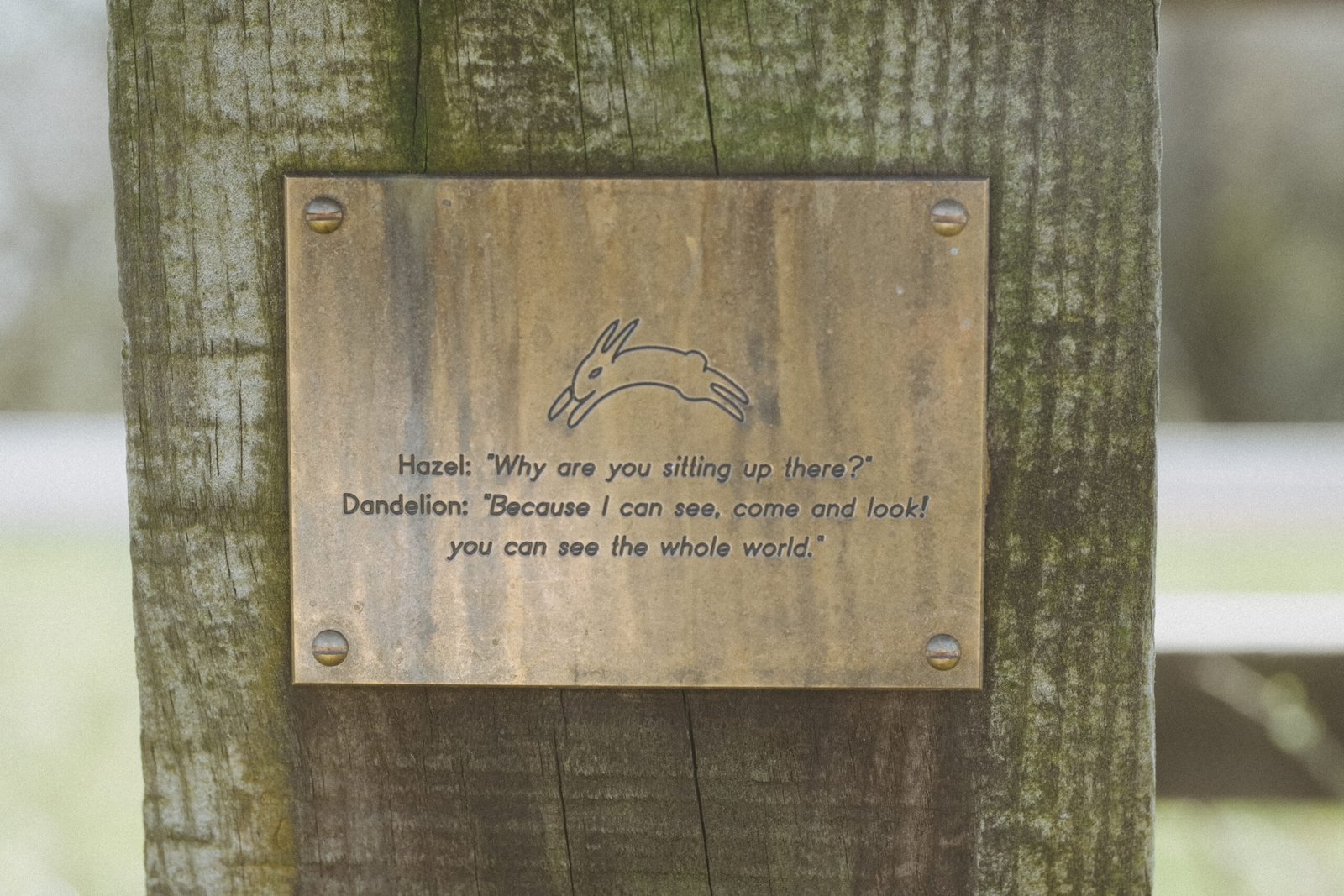

The second is a stylised version of the famous exchange between Dandelion and Hazel in Chapter Thirteen:

Hazel: ‘Why are you sitting up there?’

Dandelion: ‘Because I can see, come and look! you can see the whole world.’

The top of this plaque is adorned with a bounding rabbit. This lovely etching reminds me a lot of the film’s sequence of Fiver’s vision after Hazel has been shot at Nuthanger Farm.

‘Why are you sitting up there?’

‘In recognition of Richard Adams’.

‘Kehaar’.

‘Bigwig’.

‘Blackavar’.

The first plaque always makes me think about the Watership Down inhabitants it mentions. Whilst there are certainly rabbits living in the beech hanger, I’ve also seen them on the lower western slope, below the lane. Also up top, I have caught sight of the occasional hare. More visible are the buzzards and kestrels who are always hovering overhead searching for mice and other small animals.

It is easy to appreciate why Richard Adams loved the top of Watership Down. For all of my gripes about the fences, a visit here is always memorable. Look for the best of the place and you will find it, even if you have to work a little harder in 2025 than you did in 1970. It is still a location where the visitor can experience a real sense of peace and belonging. One of my very favourite episodes of the Watership Down podcast is when host Newell Fisher sits in the beech hanger on a cold day. You can tell he loved every second of his time there. Me, I’ve been on the top of the Down in the morning (not early, when the gallops are busy), afternoon, at sunset and in darkness. I never get tired of hearing the wind, watching the trees move with it, listening to the birds or waiting—usually unsuccessfully—for a rabbit to emerge by the hanger. In good weather a lot of walkers pass through, but when things aren’t so pleasant, or when the sun is slipping down behind Ladle Hill in late autumn, I’ve been there all alone. Never once has Watership Down felt uncomfortable, hostile or sinister. It just feels right. Looking down at the lights in nearby cottages, or across to the crane lights to Aldermaston in the east, makes you realise how remote Watership Down is in the context of southern England’s geography. You get why Fiver saw this hilltop as an ideal refuge. It is a very special place.